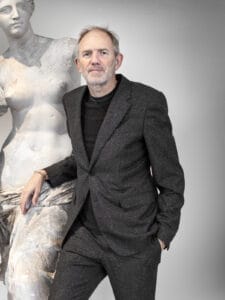

Anton Corbijn, one of the world’s hottest photographers, is currently in Denmark for the launch of his retrospective exhibition ”1-2-3-4”. Naturally, we rushed off to BRANDTS in Odense, slightly sleep-deprived out of sheer excitement, to see his exhibition and have an informal chat with him about his work.

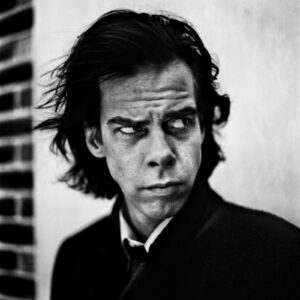

You may or may not know his name, but you will most definitely recognise Anton Corbijn’s iconic images of renowned artists like Nirvana, Depeche Mode and Tom Waits.

Despite his status as a master music photographer, film-maker and video artist, Corbijn began his career in very humble settings. Born and raised in a small village on a small island off Rotterdam, he didn’t initially have much contact with stardom. In fact, growing up in a religious family with a preacher as a father, years went by with neither a TV nor a record player. Thankfully for us, this did not quench his curiosity or love of music.

He started photographing musicians and bands in the late ‘70s, but quickly progressed to making music videos, and subsequently major feature length films such as The American, A Most Wanted Man and Life. And despite his strict upbringing, Corbijn’s hunger for mystery and broader knowledge fuelled the engine of an eminent career that is continuously boasting new accomplishments.

Read on for a sneak peek into the brilliant mind of one of the world’s most inspirational, and probably most likeable, photographers:

Why do you do what you do? What makes it all worth it?

When I was a young boy, I didn’t know what to make of my life at all. I spent a lot of time buying records, reading music magazines and the like. I knew all the details, like the names of all the drummers. Useless information, of course, but I accumulated it nonetheless, and spent a lot of my time looking at these records, fantasizing about how they were made, how people lived and how different their lives were from mine. When I finally took my first picture with my father’s camera at a live concert, I felt it was a real revelation to be connected somehow, even though it was through a camera. I wanted to discover more about photography and the adjacent world. Back then it was a real mystery for me, but that mystery has faded over the years, unfortunately. I still work with friends of mine, but my energy and focus is on making movies and doing photography projects with painters. This has really introduced a new form of mystery into my daily work.

Can you tell me something about you that not that many people know?

I think that if you look at the pictures, you get a bit of an idea of who I am. I take my work seriously, but there is also a lot of fun involved in these pictures. People dress up or do silly things. It’s partly because I don’t arrive with a big team. I just go around with a camera and maybe I have my assistant with me, but that’s it. So it doesn’t feel like I’m invading much of their world or threatening them.

A lot of creatives suffer from comparison paralysis; you look at other people’s work, compare it to your own and ultimately don’t think yours is good enough. Have you ever had that feeling?

Yeah, sure. I oscillate between desperation and elation, but I think it’s the nature of the beast. When I went through all the contact sheets to find these pictures for the exhibition, it was so depressing for me; to look back at my life and all these shoots and think “not a good picture, not a good picture, not a good picture”.. But then you finally find a good picture and it makes it all worth it.

How has technology changed the photography industry?

Oh, quite drastically and dramatically. Everybody is a photographer now, so it’s very democratic in a sense. There’s an imagery overload, so it’s really hard to get any message across in photography these days. And anything can be manipulated, so the ideal of the camera being the truth teller is also gone. If I were young today, I’m not sure I would have chosen the same career path. I would probably have been a painter instead.

You brought up the camera as a truth teller. Has looking through the eyes of the camera ever revealed something to you about a person that you had not seen by looking at them through your own eyes?

Well, pictures are frozen moments in time, and this gives you time to dissect them and discover more things afterwards than while you were taking the photos. I once took a photo of Nelson Mandela standing with both his hands up in the air, smiling. It wasn’t until I got home and printed that I saw there was a small bush of roses next to him that had the exact same shape. It was totally random and just a beautiful find because I hadn’t noticed the similarity of shape when I took the picture.

I’ve always wondered why you never took a picture of Aerosmith?

I actually did take a photograph, but I didn’t like it, so it’s not in the exhibition. And the way Steven Tyler looked at my girlfriend.. he’s not going in my book! I’m kidding, of course. There are quite a few people who are not in the exhibition, I’ve probably photographed five times more than what you can see here.

You’re quite productive! Are you still doing photography besides the video and film-making?

I still do quite a lot of photography actually. I’m in New York and Chicago next week for shooting. But I don’t shoot everyday at all. I did all the handwritten captions on the pictures in the exhibition, and I thought, ”Oh God, I took a lot of pictures in the early 80’s. I must never have been home!”

Speaking of, where is home for you?

I left the UK in 2008. I still have an office there, and I still root for the English football team, not the Dutch. After 30 years of living in the UK, the culture is more engrained in me than the Dutch culture. But I feel very at home in Holland. I realised, when I came back in 2008 and did so much stuff on my bicycle again, that luxury really lies in the simple pleasures.

I came to England in 1979 and I remember riding on my bike with my girlfriend sitting on the back, like you do in Holland. That’s how I grew up and doubling on a bike is still perfectly legal. We were cycling through Oxford Street, and this whole bus of policemen stopped and one of them shouted “What are you doing?!”. “Well, we’re cycling”, I answered. And he said, “There are two people on the bicycle!”. And I answered, “Yeah well, like in Holland”. And he said “If the law here had allowed two people on a bike, there would have been two saddles!”. And so we had to get off and walk. In hindsight he probably saved my life.

So it feels good to be back in Holland then?

The lifestyle is much more pleasant than in London. London is exciting and there are always a lot of things going on, but unless you have a lot of money, it’s a tough life. It’s easier to enjoy life in Holland, like I imagine it is here in Denmark.

How long have you been in Denmark? And how are you finding it so far?

Almost a week. I haven’t picked up any words yet though. Lars Ulrich always tries to teach me how to say “goddammit” or something, but I keep forgetting how to say it.

Oh, “for helvede”! Well, practice makes perfect.

Oh yeah, “for helvede”! Anyway, I haven’t explored much of Denmark yet. In the 1980’s I did a video with Depeche Mode in Randers, and I also did a recording in Aarhus. I like that part of Denmark, lovely landscape. I’ve been to Copenhagen quite a few times, and to Louisiana and Kattegat.. I’ve photographed a few Danes, too. Helena Christensen, Lars Von Trier, Lars Ulrich and of course Saybia and Søren Huus. I really wanted to photograph Per Kirkeby, but he unfortunately passed away before I got the chance.

What is your most memorable experience in photography?

It’s difficult to bring it down to one experience. Some of my photographs have become very iconic, so these pictures naturally spring to mind first. But I have beautiful memories of some shoots in the 70’s, because it was just exciting times, and it’s hard to keep excitement going when you know so much about your field of work. You gradually lose your naïveté. But because I travel to meet the people I work with, all my pictures carry a story. If you’re a studio photographer, people usually come in, have a cup of coffee and then leave. But the travelling and different locations have made each project a real journey.

Where are you in a year from now? Are there any new movies or projects in the pipeline?

I’m shooting a film next year. That is, I’ve been working on a film that hopefully happens next year, and also the TV series. But in the film industry you always have to have a few balls in the air because so many things can change, or don’t happen at all. There’s very little money involved in taking a photograph, so people take risks much easier, which is in stark contrast to the film industry where there are millions involved, and people and opinions to take into account. It’s a whole different story.

Would you say that’s the most difficult part of film-making?

Yes, I’m used to depending on my gut feeling in photography, and it’s a very low-key and quick way of working. With film-making you pretty much have to put aside a whole year of your life. That can be tough, but the great thing is that you may end up creating something that a lot of people will see. My learning process in photography has stagnated, but with film-making, I have had to learn how to tell a story, and I’m sure this new knowledge will be beneficial for my photography in the end.

When I started doing music videos in the early 80’s, the videos would look like a photographer making a film because the camera never moved, but in the end, the videos became much more filmic. Simultaneously, the experience of making videos worked back into my photography. I started to use stylists and props, and I became much more actively involved in what happened in front of the camera.

What’s the most challenging about portrait photography in your opinion?

I have always felt that if you take a picture of a person, the picture not only has to say something about that particular person, but also say something about the photographer. Why else would you have one photographer take the picture and not the other? So the challenging part is taking a photograph that stands out, and also producing an end result that doesn’t resemble anything you’ve ever seen before.

How long did it take for you to develop your own signature style?

In the early 70’s, I had maybe only one picture a year turn out to be the kind of picture I wanted to take, but in the 80’s I produced a lot more pictures that felt like “me”. But I’ve always felt that it’s your disability to do it any other way that ultimately comprises your style. You get stuck with a specific way of shooting because you simply can’t do it any other way. And then after a while people start saying “Oh, that’s your style”. So my style was not consciously chosen, it chose me.

Is there anything else you would like to share with us, a funny story or the like?

Yes, I actually have one relevant story. When I came to London in 1979, I went to this magazine called New Musical Express, which used to be the bible of music labels. They ceased to exist last year, but they were like the Rolling Stone Magazine of Europe. I moved to London for Joy Division, but also because I went to this magazine and asked them if they could give me work. They agreed, so I came back half a year later and said “Hey, I live here now, could you give me some work?”. And this guy couldn’t remember me, but he took me around to all the writers’ desks, nonetheless. “This is Anton, he’s from Holland and he’s a good photographer. Has anybody got some work for him?”. All the typewriters stopped, clearly unimpressed, and then went back to typing, and then somebody started singing: “I hate the fucking Dutch, they live in windmills and wear clogs”. And then somebody added – and that’s where the relevance is, at the end of the song – “but most of all, I hate the fucking Danes”, ha ha! It was an old punk song, I think, and when he sang “the Danes” I was like “Yes, they’re worse than the Dutch!”

Anton Corbijn may have become culturally assimilated with the British, but he has managed to keep some of the endearing Dutch directness! Regardless, this bluntness is a sign of affection in the Netherlands, so let us take this opportunity to thank you, Anton Corbijn. Thank you for your stories, for your honesty and for the everlasting impressions you are giving to this world. We at RockZeit are excited to see what 2020 will bring.

The exhibition 1-2-3-4 can be seen at Brandts – Museum of Art and Culture in Odense, Denmark until November 17, 2019.